In 2022, ByteDance released a paper detailing their Monolith real-time recommendation framework, which is the core system behind the BytePlus Recommend product. Monolith tries to address two common issues in large scale recommenders:

- Models usually rely on large embedding tables that grow over time and common approaches like the hashing trick result in lost feature expressiveness

- Concept drift, i.e., the change in distribution of user data changes over time, even within a single hour, requires consistently learning from recent data

Their solution is simple - build a collision-free embedding table and build an online training system. But of course that is easier said than done, especially at large scale. So let’s dive into it!

Handling large embedding tables

Throughout the paper, the authors describe a general deep learning recommender system that is split into embedding generation followed by dense layers. For this post, let’s assume a simple model where we embed user ID and video ID, and then we concatenate the embeddings and pass them through an MLP that outputs scores for multiple tasks, e.g., like, share, etc.

The issue is that the embedding table needs to grow as new users and videos come in. To handle this, a common trick is to use hash functions to map IDs into a smaller table. However, while this reduces table size it does allow hash collisions, i.e., mapping two different users or videos to the same ID, which can deteriorate model quality. Monolith solves this by designing a collision-free hash table and filtering out stale IDs.

So how does one build a colision-free hash table? Simple, they rely on cuckoo hashing, which still relies on hash functions but allows adding new keys without collisions while maintaining an amortized O(1) time complexity for insertions! This completely addresses the collision problem so now we just need to prevent uncontrolled growth of embedding tables.

To reduce table size, there are two important observations:

- Most IDs will rarely appear in the training data while others will be very popular, i.e., the distribution is long tailed

- Stale IDs, i.e., inactive users or very old videos, will not contribute to the model while still taking up space Given these observations, the solution is simple - filter out from the table stale IDs (using an expiration timer) and infrequent IDs (with an occurrence filter).

That’s it! We now have the ability to hold a lot of embeddings without collision in an efficient manner. Next up, let’s discuss how we can prepare data for online training.

Streaming data

As mentioned earlier, our goal is to have our model adapt to new user preferences as quickly as possible. For example, think of the TikTok algorithm - if a user begins having a few positive interactions with a particular type of content, the system is able to learn this new preference and lean into it quickly. This can be done by training on user data as quickly as possible - and for that, you need a good data pipeline.

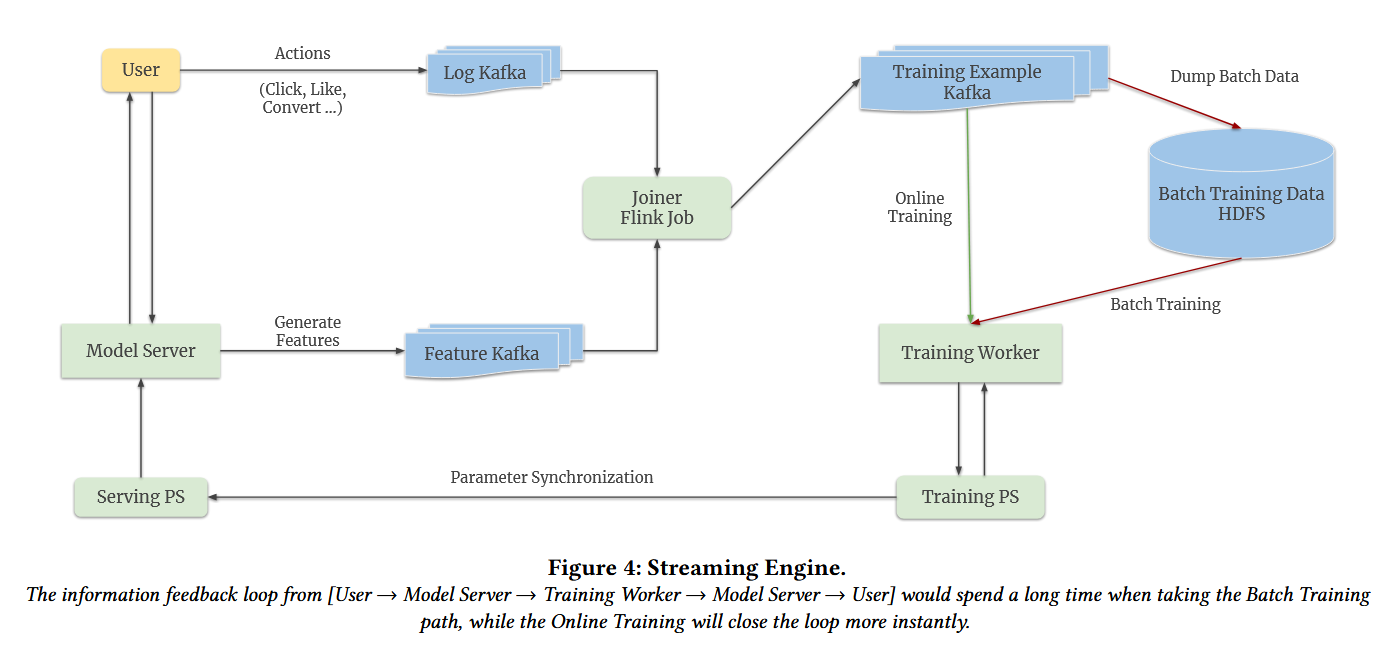

Monolith includes a streaming engine that handles data collection and processing both for offline batch training and online training. They log user actions and their point-in-time features using Kafka, join them using Flink, and then place them into a final Kafka queue of training examples. This queue is then read from by an online training worker and by a data storing worker. Fairly simple but there are a few problems.

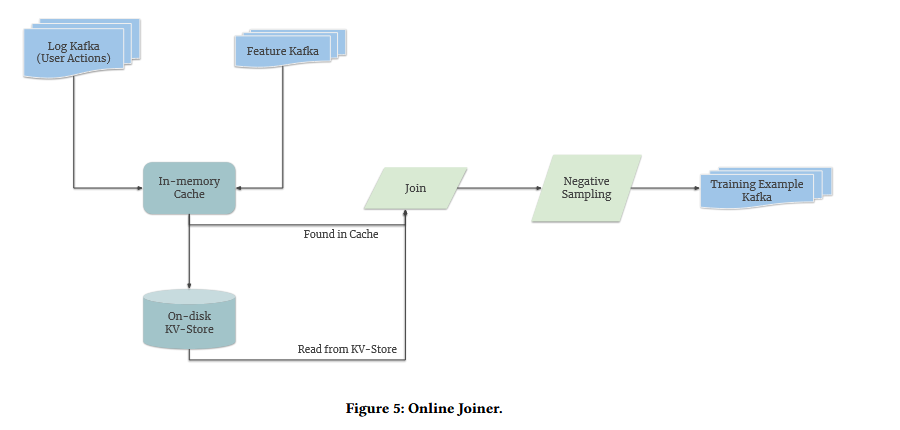

One problem is delayed user actions. For example, it may take users a few days to buy a product after being shown a video ad. So we need to log the ad view event, the purchase event days later, and then merge the two into a single training example. Figure 2 shows their solution to this problem. They simply keep an on-disk key-value store with an in-memory cache. When the action log arrives they pull the original features (user and video features) from the cache or from the key-value store if too much time has passed.

The second problem is the dataset can have too many negative events, making it hard to train the the model. Figure 2 also shows the solution to this - sample only some negatives and later apply a log odds correction to ensure the online model is unbiased!

We now have a streaming queue of training examples ready for online training, so let’s jump into it!

Training

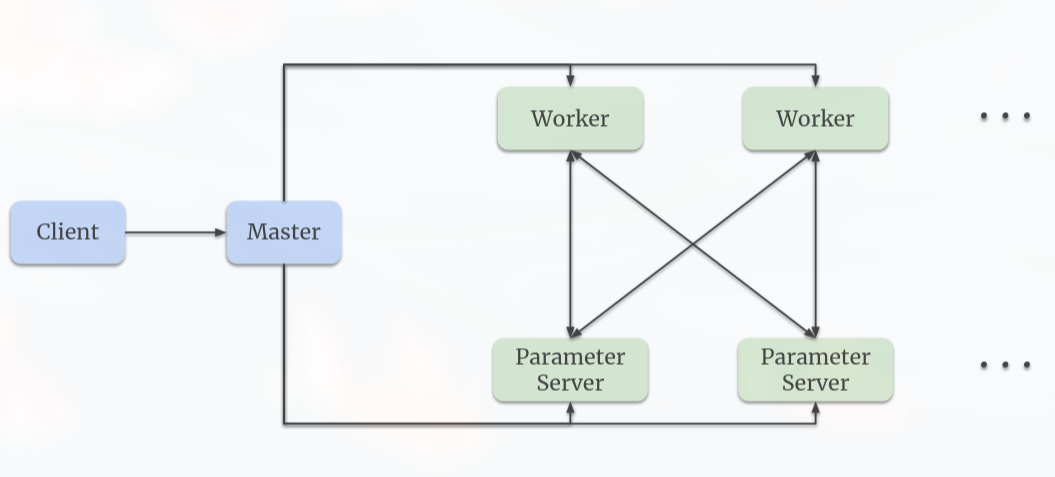

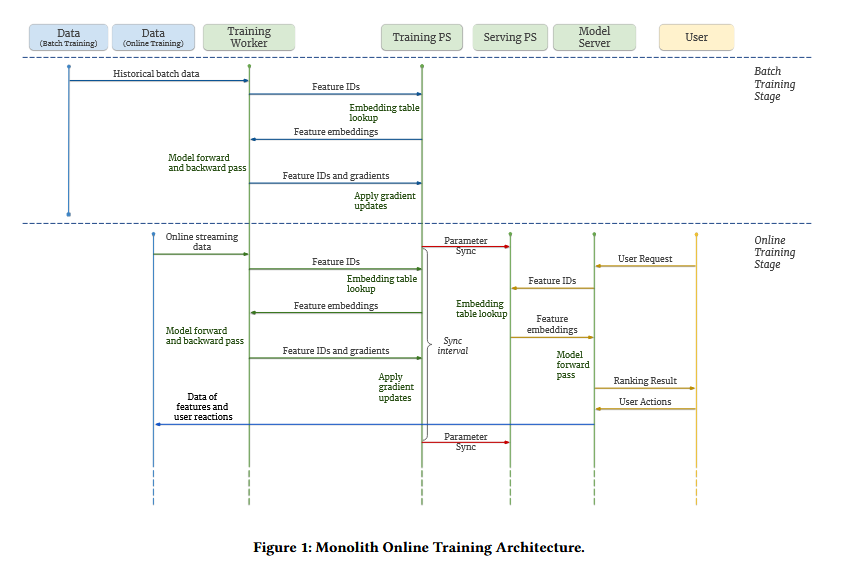

Monolith follows TensorFlow’s Worker-Parameter Server (PS) architecture, where parameter servers store and update model parameters while workers perform computations. The model is hosted in chunks across multiple PS, with different PS for online serving and training.

Figure 4 describes the training system architecture. For online training, the flow is:

- Training worker reads data from Kafka

- Sends feature IDs, e.g., user ID and video ID to training PS, gets embeddings and dense parameters back

- Runs forward and backward pass

- Sends IDs and gradients back to PS, which applies the updates

Every once in a while, they sync the training PS with the serving PS. One important note is that transferring a multi-terabyte model from training to serving would be infeasible in terms of network and memory. Instead, they do the following:

- Keep a set of touched IDs, i.e., embeddings trained since the last sync

- Push the subset of sparse parameters with a minute level interval

- Update dense parameters much less frequently

This works because only a small subset of IDs are trained in between in each update and because dense parameters move slowly in online training - unlike the IDs, dense parameters are updated with each training example, so they move much more slowly.

Results and conclusion

They conduct offline experiments and online experiments on an unspecified model. Across their experiments, they saw slightly increased AUC from the collision-free hashing and from reducing the sync interval from training and serving PS.

In conclusion, I think that most of this work isn’t particularly groundbreaking in its design ideas and that the final results are not that great. However, being able to implement and execute real-time recommendations at scale is a significant achievement. Furthermore, the paper presents a clear blueprint of how to build such a system which is a great starting point for any company/engineer looking to experiment with real-time recommendations!